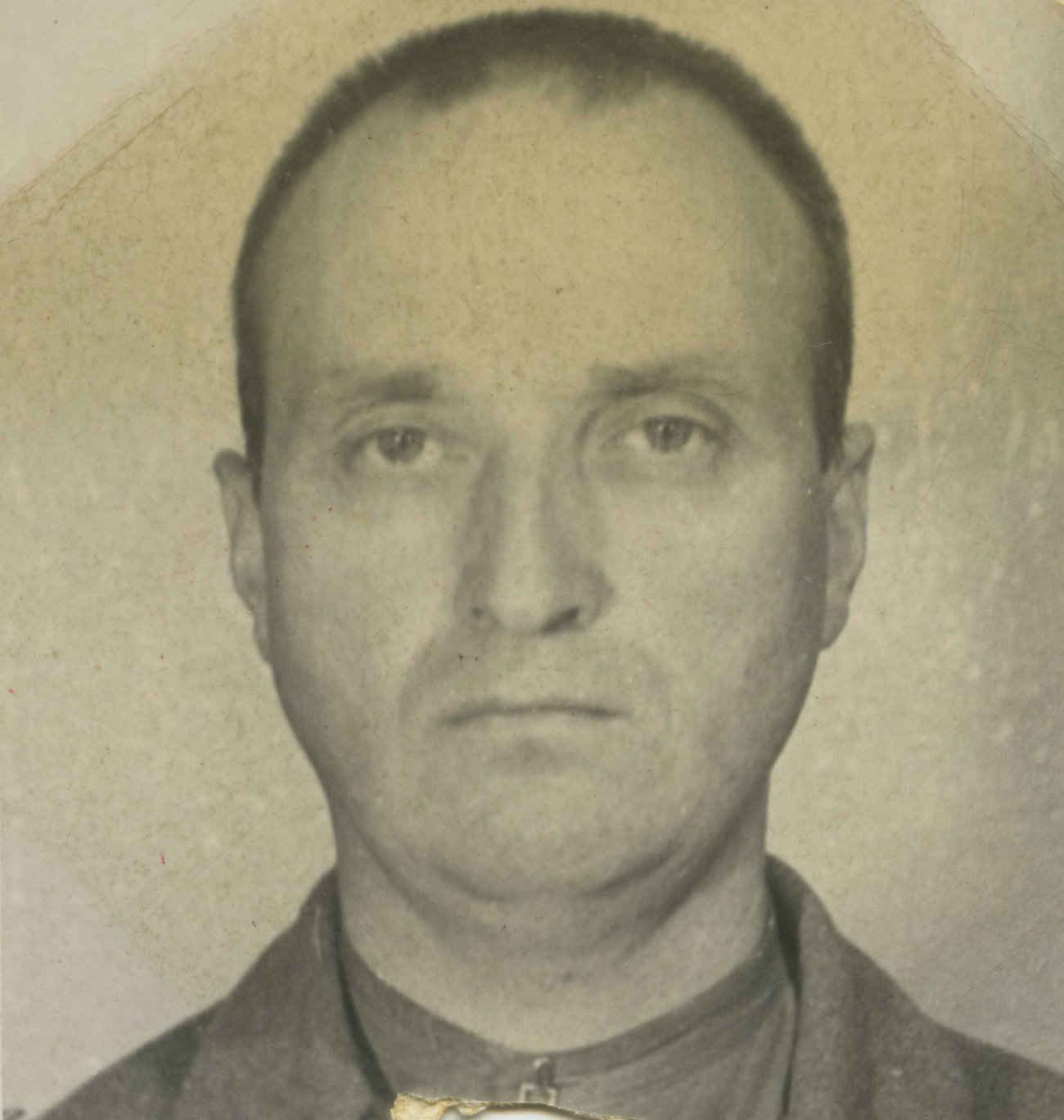

Johan Alssema was born on 8 December 1901 in the village of Haren, in the province of Groningen. He was the son of Hendrik Willem Alssema, a metalworker, and Diederika Fikkers, a homemaker. At the age of eighteen, he married Auktje Oostra, with whom he had three sons. Their marriage ended in 1927, and Alssema remarried twice more — first to Niessien van der Tuuk in 1936 (divorced in 1948) and later to Anna Maria Groen in 1961 (divorced in 1967). He spent much of his life in Groningen and Stadskanaal, and after the war, settled in Amsterdam.

Before the Second World War, Alssema worked as a policeman and civil servant, leading a relatively quiet life. But his ambitions and authoritarian character drew him toward the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB), the Dutch Nazi party. When the Germans occupied the Netherlands in 1940, Alssema joined the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the feared German security service, and soon gained notoriety under the name “De schrik der Veenkoloniën” — The Terror of the Peat Colonies.

Alssema was ruthless, often described as more merciless than the Germans themselves. He took part in raids, arrests, house searches, and interrogations of resistance members and those suspected of hiding Jews or fugitives. Witnesses later recounted that he had no sense of compassion — “The Germans sometimes showed pity,” one said, “but Alssema never did.” He was also linked to multiple cases of torture and murder, particularly in the northern provinces of Groningen and Drenthe.

After the liberation in 1945, Alssema was arrested and brought to trial. His courtroom was packed — according to Nieuwsblad van het Noorden, the public galleries were so crowded that people fainted while waiting to witness the proceedings. Testimonies painted a grim picture of his cruelty, and he was sentenced to death and permanently stripped of his voting rights. His death sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment, and eventually reduced to a seven-month prison term.

On 19 October 1959, Alssema was conditionally released. However, because he had voluntarily served a foreign occupying power, he lost his Dutch citizenship and became stateless. As such, he was required to register with the aliens police, report any changes in residence or employment, and was barred from traveling abroad or voting. Many Dutch collaborators shared this fate in the postwar years.

In 1953, a law was passed granting amnesty to many who had become stateless through wartime collaboration. Alssema lived quietly in Amsterdam for the rest of his life, far removed from the northern countryside where his name had once inspired fear.

He died in 1985, a forgotten figure of one of the darkest chapters in Dutch wartime history — a man whose choices turned him from an ordinary civil servant into one of the most feared collaborators in the northern Netherlands.