Walter Süskind was born on 29 October 1906 in Lüdenscheid, Germany, into a Jewish family headed by Hermann Süskind and Frieda Kessler. He grew up with two younger brothers, Karl and Alfred, and lived a fairly ordinary life before the rise of the Nazi regime changed everything. As antisemitism in Germany became more dangerous, Süskind fled in March 1938 to the Netherlands. His original plan was to continue on to the United States, but events soon forced him to remain in Amsterdam.

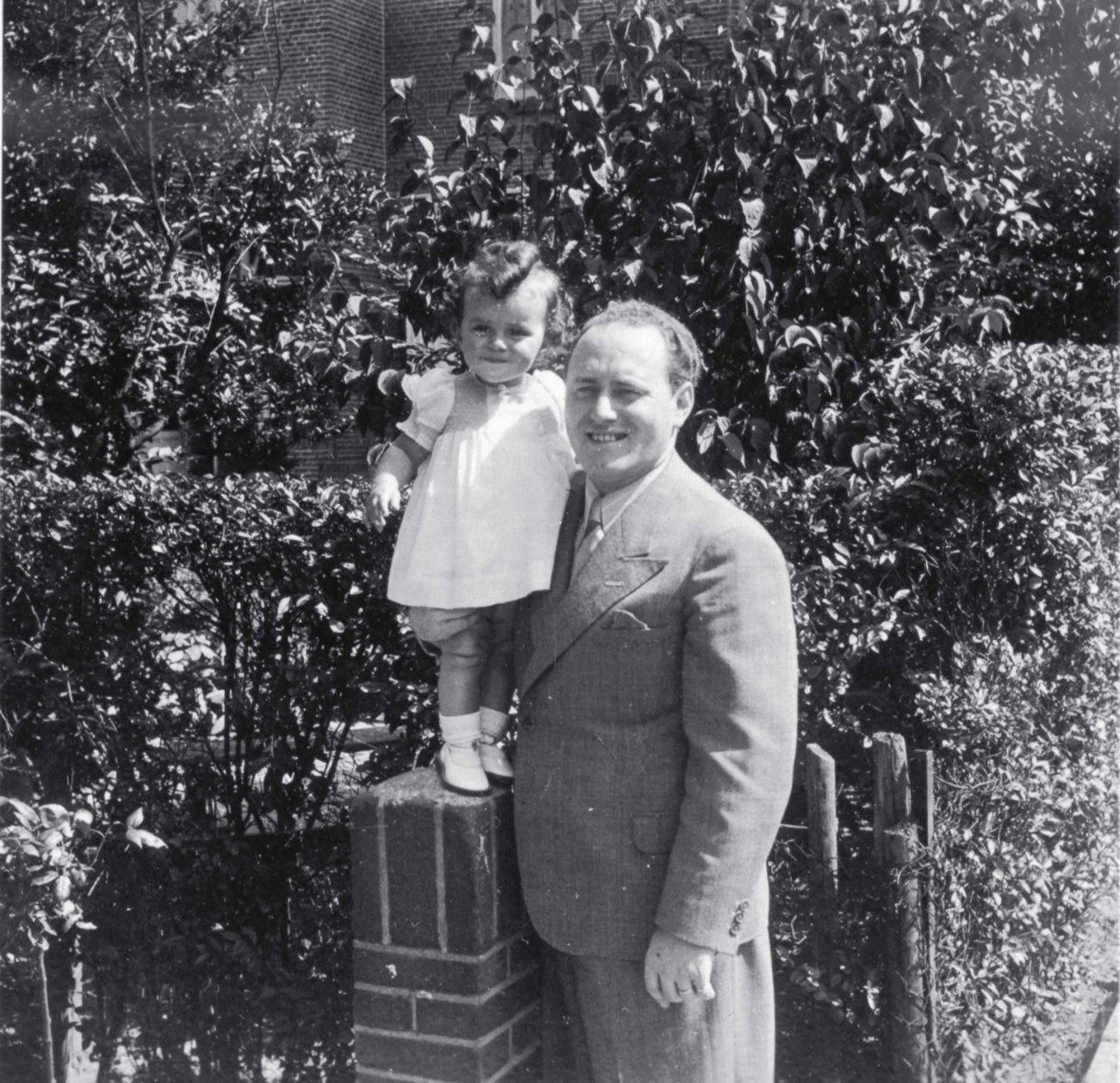

Before the war, Süskind had worked as a manager in a margarine factory, but in the Netherlands his life took a very different direction. He settled in Amsterdam with his wife Johanna Natt and their daughter Yvonne, living on Nieuwe Prinsengracht in the city center. When the German occupation of the Netherlands began, he became involved with the Jewish Council of Amsterdam, an organization created by the Nazis to administer Jewish affairs under strict German control. Süskind was appointed manager of the Hollandsche Schouwburg, a former theater that the occupiers turned into a gathering point for Jews before deportation to the Westerbork transit camp.

This position placed him at the heart of the deportation system, but also gave him an opportunity to resist it. Süskind built working relationships with German officials, including SS officer Ferdinand aus der Fünten, which allowed him a degree of trust and access. Behind the scenes, he exploited this position to manipulate registration records, especially those involving children. By altering paperwork, delaying transport lists, and removing names, he created chances for young lives to disappear from the system.

Directly across from the theater stood a nursery where Jewish children were temporarily housed after being separated from their parents. Together with the nursery’s director Henriette Henriques Pimentel and fellow resistance worker Felix Halverstad, Süskind helped organize a plan to smuggle children out. A nearby teacher training college, led by Johan van Hulst, became part of the escape route. Children were taken through a garden path into the school, then hidden in backpacks, shopping bags, and laundry baskets. From there they were transported by train or tram to safe addresses in rural areas such as Friesland and Limburg. A local resistance network, including Piet Meerburg and the Utrecht Children’s Committee, found hiding places and families willing to shelter the children. Through these efforts, around six hundred Jewish children were saved from deportation and likely death.

In 1944, Süskind and his family were deported to Westerbork. Although he was briefly allowed to return to Amsterdam due to his contacts with German officials, he chose to go back to the camp to remain with his wife and daughter. He attempted to continue helping others escape, but conditions by then had tightened severely. Both his wife and daughter died in Westerbork, and Süskind himself died on 28 February 1945 at an unknown location in central Europe during a forced evacuation, known as the death marches.

After the war, his courage gradually became more widely known. In 2012, a Dutch film titled Süskind brought his story to a broader audience. His life has also been described in books such as Süskind by Alex van Galen and The Heart Has Reasons by Mark Klempner, which place his efforts within the wider history of those who risked everything to save Jewish children. Today, Walter Süskind is remembered not as an official of a tragic system, but as a man who used his position to defy it and to give hundreds of children a chance to live.